The Truth About Recessions

This week, we diverge from our normal chart talk to focus on the economy, as the word "recession" is now on virtually every one's lips, provoked by a lot of misinformation.

First, there seems to be a general understanding in the media that the definition of a recession is two consecutive quarters of declining GDP. According to the good people at the national Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), who are the official arbitrators of business cycle chronology, a recession "is a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and that lasts more than a few months." The committee goes on to say that each of the three criteria—depth (how much output is lost), diffusion (the breadth of the decline) and duration (how long it lasts)—need to be met individually. However, extreme conditions revealed by one criterion may partially offset weaker indications from another. By way of an example, they cite the 2020 situation by concluding, "the drop in activity had been so great and so widely diffused throughout the economy that the downturn should be classified as a recession even if it proved to be quite brief". No two quarters of back-to- back GDP decline here, just a two-month waterfall. In other words, one size does not fit all.

Calling a recession is clearly more of an art than a science. From our point of view as investors, the question is not so much "Is there going to be a recession?" but rather "How deep will it be?" and "How long will it last?"

There's Always Another Recession Around the Corner

Throughout 20 years or so of recorded US economic history, the economy has continuously transitioned between recovery and recession. In recent decades, recessions have been a less common experience, thanks to the Fed intervening with soft landing policies, which limited the downside part of several cycles to growth slowdowns. Ironically, since 1962, the business cycle low points in the economy, be they slowdowns or recessions, have been separated by an average of 41-43 months, not dissimilar to the 41-month cycle discovered by Joseph Kitchin in the 1920s. The reason probably lies in human nature, as individuals in the economic world transition from fear to greed just as investors do in the financial markets.

It's the Depth and Duration of Recessions That's Important

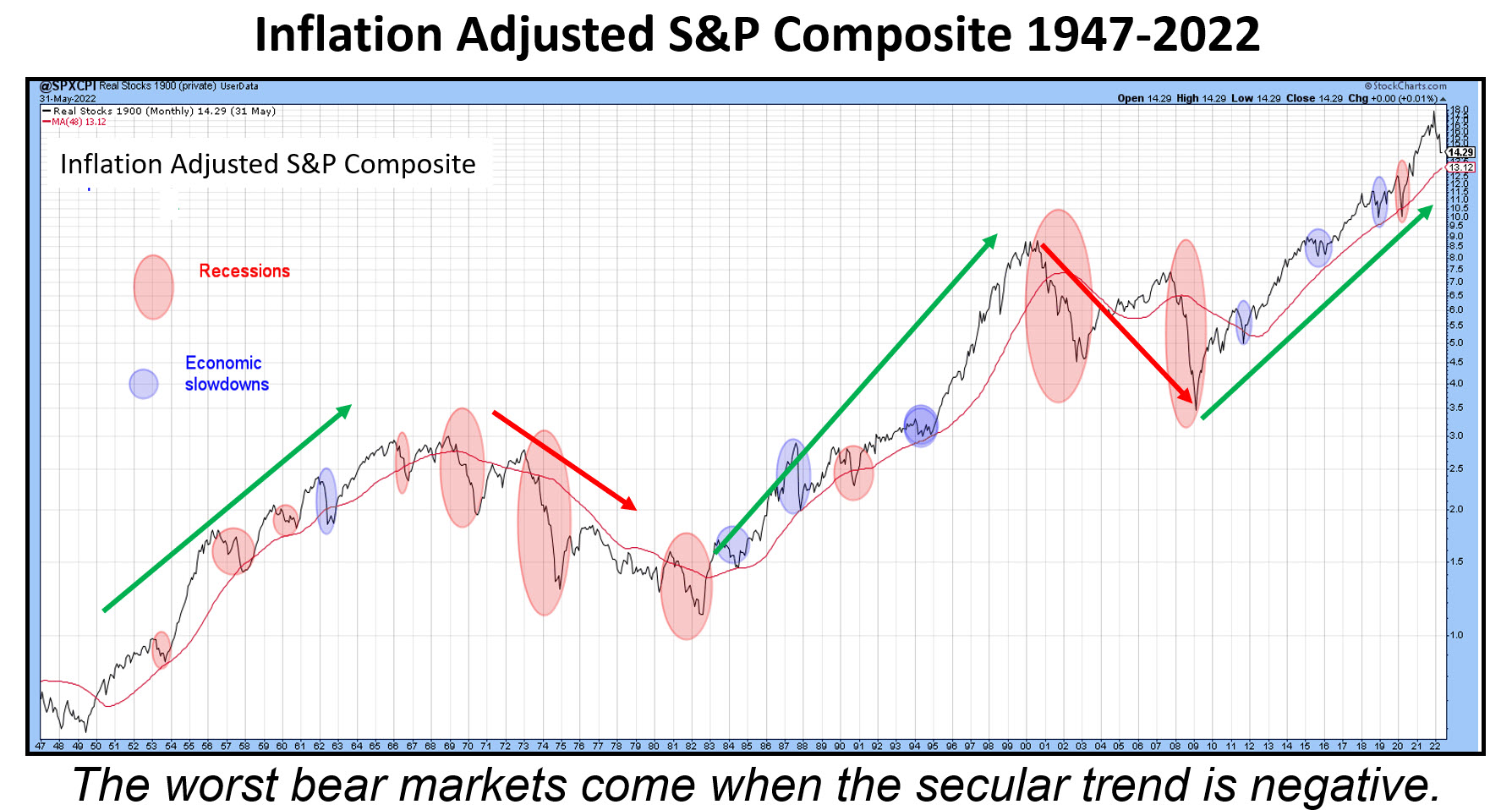

Chart 1 highlights bear trends that have been associated with economic slowdowns in blue and recessions in pink. The smaller ellipses indicate bear markets caused by slowdowns or mild recessions. The larger ones are associated with deeper and more prolonged economic contractions. At Pring Turner, we call these mild bear markets "burglars" because they have a mild and temporary effect on portfolios, whereas the larger ones, named "bank robbers," are responsible for more devastating and protracted damage. At first glance, it seems almost random as to whether a recession induced bear will turn out to be a burglar or bank robber, but Chart 2 puts us straight on that one.

Here, the S&P has been plotted on an inflation-adjusted basis for two reasons. First, from a long-term aspect, it does not help if we increase our portfolio by 50% and the CPI rises by a similar amount. Growing your assets by less than the cost of living is not that helpful. Second, rapidly-expanding inflation is caused by structural imbalances in the economy, which means more frequent and generally deeper recessions.

The arrows in the chart reflect the secular trends, green for the bulls and red for the bears. Secular uptrends are characterized by burglars and secular declines by bank robbers. Note how, during the period between 1966 and late 1982, the nominal S&P rallied overall (Chart 1). Compare that to the devastating performance by the inflation-adjusted series.

Conclusion

US equity prices have already lost 20-30%, depending on which average is considered. That means the market has already priced in a burglar, i.e. a slowdown or mild recession. It therefore represents a great buying opportunity if the secular bull market is intact. The question of whether we are in or are about to get into a recession is therefore a moot point. From an investment point of view, the real question should relate to the depth and duration of any recession, because that will determine whether the secular trend has reversed to the downside. If so, it most probably means that the current bear market will turn out to be a bank robber. I try to answer some of these points in my StockCharts mid-year outlook presentation and the question of whether the secular trend is turning in this article.

Good luck and good charting,

Martin J. Pring

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position or opinion of Pring Turner Capital Group of Walnut Creek or its affiliates.